The rules and traditions of the Japanese bear-hunting clans known as Matagi are said to date from either the 8th or 11th Century (depending on sources) and include a strict reverence for living in balance with the mountain ecosystem. BUT, their lifestyle is now under threat and, at the same time, controversial. The “need” for hunting and the complex relationship and inter-dependence between hunting and conservation is guaranteed to polarise opinions…

Their history and culture have a number of surprising spin-off impacts both within and beyond Japanese shores. Did you know, for instance, that the Matagi developed techniques found in the Japanese traditional form fly fishing known as “Tenkara” that is now gathering a global following since being introduced to the USA in 2009?

They also spread the practice of tenkara to the villages where they found lodgings as they migrated south through mountain ranges from the far North of Japan’s main island.

In fact, we were amazed to find out from our personal interviews with practicing bear-hunter Kazuyuki Yamada of Akiyamago that the Matagi used the word “tenkara” to describe that fishing method over three centuries ago.

While it is easy to see the respect, community spirit and knowledge of the natural environment shown by the Matagi – many of us, in modern society, are still likely to be shocked by the reality of the hunt…

Despite dwindling in numbers – and with an ever-increasing average age – Matagi values seem to chime with all Japanese outdoor enthusiasts. Their way of life and deep knowledge and respect for mountains and mountain wildlife inspired Yuzo Sebata when he created of a new form of mountain recreation that has become known as “Genryu Tenkara” in the 1980s. Sebata-san used Matagi footpaths, shelters and caves to help him survive

in wilderness areas as he rock-climbed, foraged, swam, rough-camped and fished mountain headwaters for weeks on end – miles from the nearest road and days from emergency help. He also spoke directly to Matagi as part of his education in ways to survive in the mountains. His adventures in turn lead to the creation of “sawa-no-bori” or “waterfall climbing” as a sport – another surprising cultural spin-off.

Famous for hunting bears, the Matagi also hunted serow (the Japanese goat-antelope or “kamoshika”), hare, duck, foxes and copper pheasant according to strict rules and DEEP knowledge of the mountain environment. That knowledge is said to be important to acquire by going out onto the mountain in ALL conditions (and not just in fair weather) – so that they can survive any sudden spell of bad weather and find their way home safely in the dark.

The depth of knowledge, for instance, extends to recognising by ear the wing-beat sounds of a completely solitary pheasant – compared to that same individual bird’s wing-beats flying in a more “territorial” style (in other words, revealing that there are other pheasants on the ground nearby!).

They also needed to know how to forage for wild edibles in the form of plants and fungi (this is another practice now closely associated with tenkara in Japan).

Controversial and complex – their strict practices are designed to avoid over-exploitation of wild game (and they do not reward the success of the individual hunter – all spoils are rationed equally between all group members)

But black bears are currently classified as threatened (and serow are now a protected species) and as already mentioned, many in modern society are likely to find the hunting and butchering shocking.

Photographer Javier Corso was the first non-Japanese person to be allowed to photograph the Matagi group of the Ani settlement during their hunt (previously only photographed Japanese photographer Yasuhiro Tanaka). As part of the Oak Stories production company, Javier spent 15 days living with the group to learn and appreciate as much as possible about the complex subject and his photographs (along with Alexandra Genova’s article) were published in National Geographic

Matagi Myths, Traditions and Spirituality

A rich, mythical story of the origins of the Matagi is reported by Mitsuo Matsuhashi (also of the Ani Matagi) in this article. According to legend, the first Matagi were two skilled archers; the brothers Banji and Banzaburo.

Banzaburo was said to have helped the goddess of Mount Nikko to win a dispute over the god of Mount Akagi – who took the form of a giant snake. In return for shooting the Akagi god through the eye with his arrow, the Nikko goddess gave him a scroll which gave Banzaburo divine permission to hunt in all mountains of Japan.

The head of every Matagi group owns a handwritten copy of that document – handed down through the generations. Matsuhashi-san says in his interview on the link above:

“Every time it is copied, however, the newly elected leader adds a few thoughts of his own, so I suspect it has changed gradually from the original. I also have a copy of that scroll at home, as well as an altar dedicated to the deity of the Matagi, a mountain goddess”.

A special carrying case for this scroll, made from animal skin, is an important common item associated with the ritual practice of hunting under this divine permission.

Another part of the story told by Mitsuo Matsuhashi describes the climax of the Dannoura battle between the Taira and Fujiwara clans – You may remember the details of the famous Fujiwara clan from our interview with one of the Fujiwara clan descendants.

The Taira forces were defeated and ran away. A group of between 500 and 1000 Taira journeyed and settled in Iida in the Shinshu region. Much later, factions of these settlers drifted towards Niigata, while others migrated to Nikko. Eventually, around 1650 AD, 18 men are said to have settled in Ani in Akita and established Ani as the spiritual home of the Matagi.

As well as the origins described – partly in legend, the true historical happenings are probably just as complex and certainly as fascinating. For instance, there is good reason to believe that Matagi culture has part of its origin in the Ainu culture. It may even be that “Matagi” is, itself an Ainu word, from matangi or matangitono “man of winter, hunter” – according to its Wikipedia entry – though Matsuhashi-san also suggests it may have meanings including “stronger than demons” or “straddling mountains”.

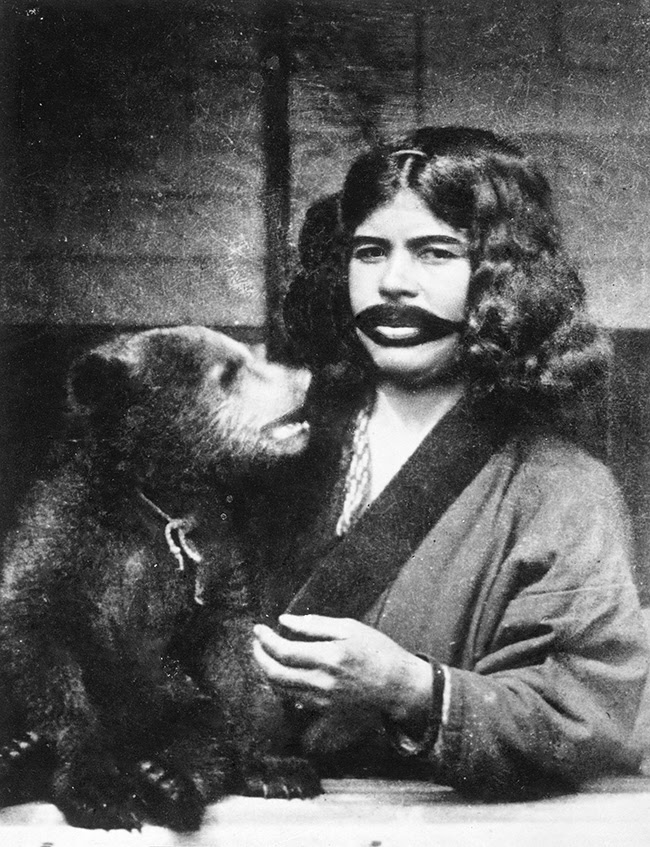

In turn the hunting and also ritual sacrifice of bears both have roots in the “circumpolar bear cult” – whose common rituals appear in the cultures of all the peoples inhabiting a ring of land-masses that encircle the top of the globe. These rituals are present in the Native Americans of North America, the Northern Scandanavian Saami, the Innuit, as well as the Northeast Asian Nivkh and Ainu peoples. E.J. Michael Witzel makes this connection in the book “The Origins of the World’s Mythologies” .

Matagi Rituals

For Matagi, “kebokai” is the symbolic ritual that returns the bear to its divine ancestors – the bear is laid out with its head and feet in particular compass directions, salt is thrown and ritual words are repeated. The similarities between this and the many same elements present in the Ainu ritual bear sacrifice “iyomante” are difficult to ignore (the main difference being that for iyomante, the bear is raised for two years before sacrifice – rather than hunted in the wild).

Even so, there is a huge crossover of the ideas that bears and other animals are the form taken by gods on earth – along with the idea of safely and respectfully guiding the killed animal to return to its divine ancestors.

The Ani Matagi lay a killed bear on its back, with its head pointing west. Partly this is practical, since if the bear is only playing dead; laying it on its front will allow it to jump up and attack you. Once death is confirmed, the bear would be covered with holly branches. The sacred chant taken from the Origin of the Yamadachi scroll is performed in order to guide the bear’s spirit to the divine realm.

There are specific chants for all parts of the hunt – before, during and after, and especially when entering the mountains.

Because these are passed down through many generations, gradual changes happen and lead to differences between the details of ceremonies performed by different Matagi groups. Following a kill, the Ani Matagi place three cuts of the heart, three of the liver and three of the loins of the bear on skewers – so that they can be held while being burnt as an offering. The significance of the three cuts is to have one for the mountain god and two more as offerings in hope of good hunting in future.

Common elements of the offerings and prayers before embarking on hunt appear to include the burning of leaves and branches – especially of Oshirobiso pine (Abies mariesii). Prayers offered in a shrine alongside the burning of the branches like incense are important preparation before setting out to hunt. The smoke and aroma produced by this ceremonial burning is believed to be the devil escaping from the branch.

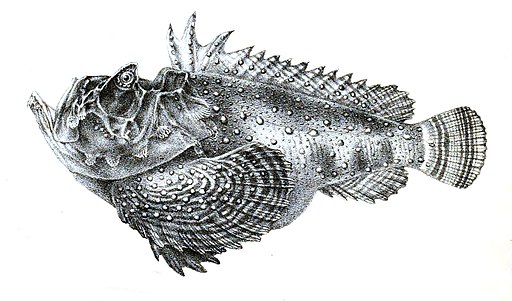

Folklore has it that the mountain deity (the Nikko Goddess) is physically very ugly – and this led to a tradition of making offerings of dried, preserved stonefish (Synanceia horrida, venomous and VERY ugly). The idea is that she appreciates offerings that are even uglier than herself!

Again, highlighted as a typical practice in “The Origins of The World’s Mythologies”, the use of secret and “correct” language (deliberately different from common language) is believed to promote balance and continued good hunting. It is a way of avoiding “pollution” of the sacred mountain environment. The language of the lands outside the high mountain environment is seen to be a potential contamination that could degrade those sacred hunting grounds.

Another, much broader, common feature is the shared consumption of the flesh of the earthly form of the gods. The ritual sharing out of the flesh between successful Matagi hunters is important ceremonially – but is also crucial in the avoidance of rewarding an individual hunter’s prowess (which could lead to over-exploitation of the wild game).

In the iyomante bear sacrifice – after raising the bear as a member of a human family (it is even reported that they would be suckled by human mothers and treated as any other child), the flesh and blood of the sacrificed animal is ritually shared between all members of the village.

This is a deeply religious act – with the consumption of the earthly form of their god being absolutely central to those practices.

In fact, it is striking to realise that the consumption of the flesh and blood of the earthly incarnation of a deity is also a central idea in Christianity…

Although the following video is in Japanese, the visuals are quite lovely and, with a little vocabulary it is possible to pick out some important themes. If nothing else, there is another underlining of the connection to tenkara at 7min 35 seconds with the footage of a freshly-caught “iwana” or white-spotted char; the classic fish of Japanese tenkara fishing and the “Shokuryoshi” (master professional tenkara anglers).

For instance, when he threads leaves onto a skewer, he is acting out putting cuts of liver, then heart,

then liver – and then finally meat from the neck, to be burned as an offering.

I really do urge you to watch the clip below, as it gives life to many of the ideas I’ve written about here. Words and themes to pick out include the following: Mukashi (long ago), Kami (spirits/gods – often believed to inhabit trees), Yama-no-kami (mountain gods/spirits), Matagi-no-kami (Matagi god(s)), Jinja (shrine), Sansai (wild edible plants gathered from the land), Kinoko (mushrooms), Sakana (fish – in this case an iwana).

Regional Differences and Changes over Time

Matsuhashi-san says “Matagi are divided into two factions, the Nikko faction and the Koya faction. The men who came to Ani belonged to the Nikko faction”.

**Author note**

**Sebata san called his personal style of tenkara “Nikko Tenkara” and published a small booklet outlining the core tactics and principles with the label of Nikko Tenkara – which is another strong link between Sebata-san’s tenkara and the philosophies and lifestyle of the Matagi**

Matsuhashi-san continues:

“Since they had to share narrow hunting grounds, there were so-called travelling Matagi as well. By the beginning of the 20th century, they were journeying considerable distances to barter their prey, and people in many places helped them out. There are Matagi in Nagano and other regions as well, but they appear to have learnt the skills from the Matagi of Ani for hunting alone, in groups of 2 or 3, in groups of 5 to 10, or in larger groups, and the traditional traps and hunting gear”.

This nomadic behaviour and trading of prey, information and culture in return for lodgings and sustenance with local residents and inn-owners is the way that both Matagi hunting methods and tenkara fishing methods were spread through many of the mountain regions of Japan’s main island. Of course it is possible – even likely – that there will have been independent invention of comparable fishing techniques in these areas and other regions of Japan at the same time.

An important factor in this exchange of survival knowledge is the strong seasonal nature of hunting (the Matagi hunts were mainly confined to winter and early spring – when the mountains are covered in snow). Even in the old days, it was almost impossible to make a living from hunting alone. In winter – there were no sources of paid income, so hunting made good sense. Matsuhashi san suggests that they survived by “gathering edible wild plants in the spring, fishing in the summer, and collecting chestnuts and mushrooms in the fall. And then in the winter, they became Matagi. Others worked on farms during the rest of the year, and then lived as Matagi during the winter. Nowadays, the busy season for Matagi is in November, around the first snow”.

Although tradition is incredibly important, technological advances to core tools have been comfortably incorporated over the Matagi’s history. For example, the central roles played by bows and spears – were first replaced by matchlock guns (based on Portuguese designs) and then, just before WWII with the “Murata” rifle (the first indigenous and standardised Japanese service rifle adopted in 1880 according to Wikipedia). Modern Matagi will now also carry modern shot-guns.

The knives carried by Matagi are incredibly important – and much of that meaning, of course, comes from how central to all survival activities a reliable and high quality knife is in mountain environments. As well as the trimming of branches, foraging/snow-cutting and basic food preparation, the reverence placed on skinning and butchering the bear makes it vital to use the highest-quality tool possible. A change in the design of these knives over time seems to be the replacement of hollow-handled knives with solid handles.

Previously, when spears were used instead of guns, the hollow handles of the knives would be perfectly fitted over the wooden shaft of a spear. Once lashed in place, a simple wooden staff was transformed into a deadly-sharp weapon.

In the same way, both the introduction of conservation protection for serow and developments in modern textiles have seen the traditional, warm serow-fur clothing transform over time. With the introduction of guns, there is also a tendency to include more brightly-coloured clothing as a way of preventing accidental shoot

On the other hand, something that has changed very little is the design of the temporary shelters in remote areas of the mountains that Matagi built to re-use from year to year. Although the materials for the steeply-sloping roof of these huts may vary between (traditional) wood to corrugated metal sheet, the design remains the same. They are built in a steep, triangular point (with only the entrance and back wall vertical) – so that all snow slides easily off. This means they are never crushed by the often extreme snow-fall that regularly ranges between 5m and 8m deep during any given winter.

As well as cave shelters, Sebata-san became very good at finding and using old Matagi shelters for basecamp locations on his climbing, fishing and foraging expeditions. I’m sure this made a welcome indulgence after camping under the infamous “buru-shii-to” (“blue-sheet”) – a blue plastic tarpaulin that can be hung from tree limbs and pegged out to form a shelter over rough-sleeping and eating quarters.

Matagi Skills

Practical Knowledge

Developing a life-long knowledge and familiarity with the mountain environment and everything that lives there is clearly essential for survival in those snowy regions. Noticing how everything changes with the seasons develops into an instinctive ability to predict and react.

“Sometimes I was taught explicitly what to do, but basically it was learning by looking. For example, when it is snowing quietly, hares usually stay in dark groves. On windy days, when accumulated snow comes crashing down from the canopies, they stay away from the trees. Hares are nocturnal, so they can’t rest in places where the snow falls heavily during the daytime. They will be in a clearing where the snow is not falling”.

Mitsuo Matsuhashi

Matsuhashi san goes on to explain that you have to learn all these habits for all different species – so that pheasants, bears and foxes all use different kinds of rest places in response to different weather conditions. By developing that deep knowledge,

it is possible for him to know where the various animals will be – even before leaving the village and heading up into the wilderness.

That variation in response to different weather conditions does not just apply to the animals that are being hunted. It is just the same for the hunters themselves to know where to find shelter in an emergency – or routes to escape rising flood-waters should the need arise. This is especially true because mountain weather can change so fast. It is also why the Matagi place such high importance on experiencing the mountain in all conditions from an early age. It’s not good enough to only be OK if the weather stays fine.

Just to prove that those changeable conditions don’t care if you are a professional or taking time out for (hardcore) recreation – Sebata-san recalls a time in the early 1990s when he and a friend were cut off for three days by rising river floodwaters (screen-grab below from this event)

Another example of the “next level” knowledge of nature would be the ability to know a bear’s intended direction just before it enters a stream or marsh where footprints disappear. It is, apparently, possible to judge whether or not a bear tends to double-back and head either upstream or downstream by the way its weight distribution forms footprints as it is about to enter the water.

Preparing for problems is such an embedded part of the culture that it should be no surprise to hear Sebata-san talk about how Matagi would often transplant iwana (white-spotted char) above impassable waterfalls. In this way, streams that previously did not hold fish became a long-term insurance policy by becoming a source of protein and energy if hunters were unexpectedly cut off in an area.

Sebata-san also took this insurance policy seriously and has been known to do the same thing (using plastic carrier bags filled with water to carry fish that he caught while fishing as he climbed over the “fish-stopping waterfall” – or “Uodome” in Japanese).

In the same way, the time invested in learning when, where and how various edible plants and mushrooms can be found is yet another type of “pre-prepared insurance policy”. The wild plants, known as “Sansai” are a prized delicacy served in the inns of mountain villages even today. In our experience, the gathering, preparation and serving of sansai with meals is also an important way of forming social bonds amongst groups of tenkara anglers.

Sebata-san told us that it was his exploration of sansai and edible fungi that gave him his love of food (and allowed him to pursue a career as a chef and restaurant owner in Tokyo). In many ways, everything that formed the passions and sources of income in Sebata-san’s life has, ultimately, been inspired by the Matagi and Shokuryoshi.

To bring this back to those inspirational cultures; the painstaking observation of the prey, edible plants/fungi, weather, habitat and the interactions of all these things over many years leads to a strong appreciation for the balance of nature.

Modern Matagi and Crossover Professions

This way of life is dying out. Although it has probably always been true that other sources of food and income have been necessary, it is clearly impossible today to sustain as a person’s only occupation. Today, licences to hunt in this way are expensive, with a complicated application procedure and difficult examinations that must be passed before they are granted.

On top of the difficulty and expense in obtaining a licence, they must be renewed every three years and hunting is strictly restricted to winter/early spring.

Many hunters work as wood-cutters and other general trades (including catching fish) in summer and the Shokuryoshi (professional fly fisher) tradition has a huge amount of crossover with the Matagi culture and way of life.

In 2017 myself and John Pearson were incredibly lucky to spend several days with Kazuyuki

Yamada at his family-run inn called “Shuzanso” in the tiny mountain settlement of Akiyamago. Growing up with the traditional trades and crafts of the mountains, Yamada-san is – at once – an Inn-keeper, Shokuryoshi, Sansai (wild plants) and Kinoko (fungi) gatherer and some-time hunter in the Matagi tradition…just like his father. The sansai he gathered and cooked with his wife (along with the iwana he caught and served) were indescribably delicious – whether lightly pickled in brine, fried in tempura batter or any number of other perfect recipes.

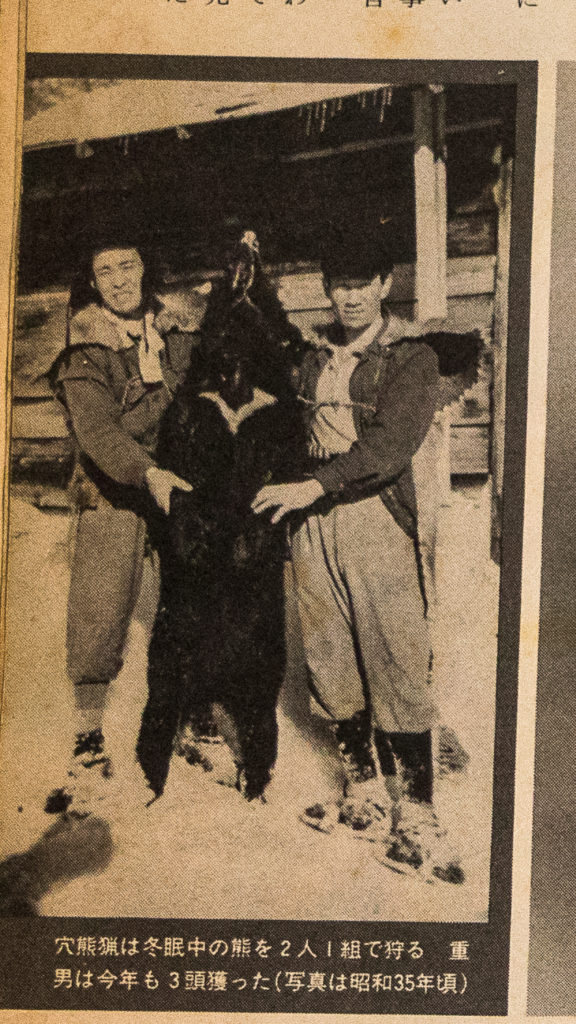

Shigeo Yamada (Kazuyuki Yamada’s father) was one of the most famous Shokuryoshi in Akiyamago during the 1970s. He is featured in a book on the Shokuryoshi and also appeared in magazines of the day (including photographs of his successful communal bear hunts). When he passed away, Kazuyuki Yamada took over the family inn.

Yamada-san told us many amazing stories during our stay – and these included many simple details that are often the most interesting. It is those day-to-day “ordinary” details that really bring these stories of disappearing cultures to life. For example, he explained that the group of hunters (sometimes up to around 30 people) will always drink strong alcohol after the hunt – No matter whether they were successful or not!

With a wry smile and a knowing chuckle that made the story all too relatable he said that the mood of those drinks obviously varies a lot, from completely “up” to “down in the dumps” – depending on whether they came back empty handed or in triumph. Not all people involved in a Matagi hunt have the same job – it is a carefully co-ordinated strategy between scouts, people flushing the bear towards the marksmen and, of course the marksmen themselves.

Kazuyuki has been the nominated marksman on probably somewhere between 30 and 50 occasions and he spoke of just how high the pressure is on you when it is your turn to take the shot. So many other people are relying on you…

How much pressure? Well, when I asked him if he was ever scared when hunting bears, he replied that the fear of letting everyone down by missing your shot was far worse. One time he heard the bear’s footsteps approaching BEHIND him and he had to stand completely still and wait until he knew it was very close so that he could be sure of a clean shot before he turned round.

He survived to tell the tale by keeping his nerve and making the shot.

The inter-connectedness of the mountain culture became apparent to us when we interviewed Sebata-san a few weeks after our time with Yamada-san. When we mentioned that we’d stayed at Shuzanso and had Kazuyuki Yamada demonstrate his hand-made horsehair lines, fishing flies and techniques, Sebata-san replied “Oh yes, I knew his father back in the day…”. It would seem that the research with Matagi and Shokuryoshi that Sebata-san completed while he developed the “Genryu Tenkara”/”Nikko Tenkara” style had brought two men together.

That strand runs very deeply through the modern practice of tenkara, since it was Sebata-san himself who solidified the word “Tenkara” as the recognised term used in fishing magazines to describe those techniques. Before settling on a concrete term, it was equally likely that articles would reference “kebari-tsuri” (literally “fly fishing”) when talking about tenkara techniques.

It seems very fitting that Sebata-san (who learned so much from the Matagi) chose the word that the Matagi gave to the ancestors of the Yamada family in Akiyamago more than three centuries before as the official label for the modern sport.

As well as giving us the basic word “Tenkara” and fundamental fishing skillsets associated with it, the Matagi culture has infused all of the modern tenkara “hobby” with common ideals and philosophies.

Although too complex to define in just a few simple words, it is important to at least recognise that these values include promoting knowledge and reverence for the landscape, the plants and the animals of the

places where fishing and hunting takes place. In other words, great respect and high value is afforded to people who want to learn the knowledge and techniques that have been developed over many generations. Cementing this with your own diligent studies of nature, conditions and the behaviour of the fish you wish to target are also equally prized. Interestingly, outside of professional Shokuryoshi who catch fish to sell using tenkara, it is the sporting/recreation tenkara anglers who are at the forefront of a growing “Catch and Release” ethic in Japan.

The ideals of mobility/travelling on foot to reach the most suitable areas and self-reliance – but with strong shared community responsibility and friendship are very strongly evident in Japanese tenkara. As with most close human relationships, there is a central role of sharing of food and strong drink (plus the amazing post-fishing “onsen” hot spring baths). For me, the sense of camaradarie and love of providing food and good company for all who share that interest are incredibly attractive elements of the tenkara community.

Of course, mobility often goes hand in hand with using only what is necessary. That, in turn, forces you to place great importance on developing the skills and knowledge to use those simple tools to their greatest potential. It is the paradox of that the simpler your gear – the more nuanced and comprehensive your knowledge needs to be.

Finally, when you know a little of the background and the entangled histories and cultures of the mountain subsistence hunting, foraging and fishing in Japan, it is absolutely obvious why foraging for sansai (mountain plants) and kinoko (mushrooms) are also a natural part of the whole experience.

You can even see how these philosophies are a natural fit for those who are drawn to all outdoor activities – including hiking, climbing, rough-camping and especially ultralight backpacking.

The influence of the Matagi and all related mountain cultures are strong elements of the modern recreation. From my own experience, I can definitely say that it adds greatly to the enjoyment and addictiveness of belonging to the global tenkara community too.

Paul Gaskell

If you enjoyed this, please consider sharing the page link and pass it on…